Olafur Eliasson's Turner Colour Experiments (2014) at Tate Britain

As reviewers of Tate Britain's Late Turner – Painting Set Free have pointed out, there is much more to the artist's final years than the 'sublimely empty pictures'that regularly get compared to the work of abstract artists. The last Turner show I went to, at Margate earlier this year, paired him with Helen Frankenthaler and two years ago the Tate itself mounted an exhibition that made the link with Cy Twombly's later paintings. Visiting this new exhibition last weekend, I came ready to enjoy the art anachronistically: the abstract expressionism of Turner's Rough Sea (1840-5), the minimalist sequence of blue and grey sky studies (similar to those in the Channel Sketchbook viewable at Google Art) and of course those famous visions of Venice dissolved in light. The temptation to forget Turner's subject matter and see his work in terms of pure colour was also encouraged by the presence of Olafur Eliasson's Turner Colour Experiments (for a discussion of these, see BLDGBLOG). But ultimately I found I was just as interested in the way Turner persisted with history painting, where his spectacular effects seem often to magnify rather than overshadow the incidents they depict, drawn from Shakespeare, the Bible and the classics. For this post I want to focus on one of these, Cicero at his Villa, which Turner exhibited in 1839.

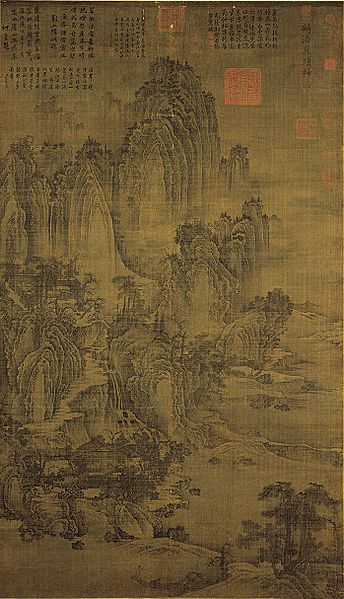

J. M. W. Turner, Cicero at his Villa, 1839

I have written here before about the appeal of bringing the work of Latin writers to life by imagining them in their setting, as Gilbert Highet did in his classic study Poets in a Landscape (1957). In 1819 Turner was in Italy, sketching at Frascati, which, according to a travel book he owned, was the site of Roman Tusculum. There he would have pictured Marcus Tullius Cicero, who wrote Stoical essays there (the Tusculan Disputations, 45 BCE) on such cheerful topics as grief of mind, bearing pain and contempt of death, two years before being killed as an enemy of the state. However, Turner was approaching Cicero through the lens of art, because, as his sketchbook makes clear, he was looking for the site where his admired predecessor, Richard Wilson, had set Cicero and his Friends at his Villa. This painting, first exhibited in 1770, is usually identified with Arpinum, but Turner would have seen another version (see below) which its owner called Cicero at Tusculum. Another source for Turner's painting may have been 'The Pleasures of Memory', a long poem that brought Samuel Rogers literary celebrity when it appeared in 1792, which mentions Cicero at Tusculum. Thus there are various paths that lead from Turner's picture back to its classical source and the three texts below (all referred to in a 1981 article by William Chubb) show how art drawn from landscape leads back to art again.

Richard Wilson, Cicero with his friend Atticus and brother Quintus,

at his villa at Arpinum, c.1771-75

(1) First there is Turner himself, drawing a parallel between Wilson and Cicero in a lecture called 'Backgrounds, Introduction of Architecture and Landcape' which he delivered in February 1811. This can be found in an old edition of the Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes - the reason it is not widely published is presumably that it is not very well written (Roger Fry tried to transcribe it and gave up saying that "it would be unfair to Turner to publish work that only shows his weaknesses"). Towards the end of the lecture, Turner regrets the fact that Zuccarelli's 'meretricious'paintings

'defrauded the immortal Wilson of his right and snatched the laurel from his aged brow. In vain did ... the Cicero at his Villa sigh for the hope, the pleasure of peaceful retirement, or the dignified simplicity of thought and grandeur, the more than solemn solitude that told his feelings. In acute anguish he retired, and as he lived he died neglected.'(2) Then there is the passage on Cicero that Turner marked in his own copy of Rogers' Poems (1827). Turner knew the poet and illustrated the long poem Italy that Rogers based on his travels (fit was from Italy that Rogers wrote to a friend: 'Oh if you knew what it was to look upon a Lake which Virgil has mentioned & Catullus sailed upon, to see a house in which Petrarch has lived.') In 'The Pleasures of Memory', Rogers describes 'the charm historic scenes impart' and refers to the time Cicero (Tully) visited Syracuse a hundred and sixty years after the death of Archimedes, to find the Sage's grave unregarded and overgrown.

(3) Finally, Cicero. At various times he owned villas at different locations, so that Wilson was able to paint another Cicero-related view (below) that combines Italian light and classical allusion. Cicero's Arpinum villa was used as the setting for his book on law,De Legibus. This begins with the scene Wilson depicts in the painting shown above, where Cicero (Marcus), his brother Quintus and friend Atticus are looking at an old oak tree associated with the Consul Gaius Marius (157-86 BCE). Thus the poignant capacity of landscape to preserve fragments of culture, which Wilson, Rogers and Turner experienced in Italy and exemplified in their art and poetry, can be found in De Legibus described by the writer who inspired them. Cicero's dialogue refers to his own earlier poem, and to a palm tree on Delos that takes us all the way back to Homer.'So TULLY paus'd, amid the wrecks of Time,

On the rude stone to trace the truth sublime;

When at his feet, in honour'd dust disclos'd,

The immortal Sage of Syracuse repos'd.

And as his youth in sweet delusion hung,

Where once a PLATO taught, a PINDAR sung;

Who now but meets him musing, when he roves

His ruin'd Tusculan's romantic groves?'

'Atticus. —This is the very grove, and this the oak of Arpinum, whose description in your poem on Marius, I have often read. If, my Marcus, that oak is still in being, this must certainly be it, but it appears extremely old.

Quintus Cicero. —Yes, my Atticus, my brother’s oak tree still exists, and will ever flourish, for it is a nursling of genius. No plant can owe such longevity to the care of the agriculturist as this derives from the verse of the poet.

Atticus. —How can that happen, my Quintus? How can poets bestow immortality on trees? It seems to me that in eulogising your brother, you flatter your own vanity.

Quintus. —You may rally me as much as you please, but as long as the Latin language is spoken, this oak of Marius will not lose its reputation; and as Scævola said of my brother’s poem on Marius, it will “Extend its hoary age, through countless years.” Do not your Athenians maintain that the olive near their citadel is immortal, and that tall and slender palm tree which Homer’s Ulysses says he beheld at Delos, do they not make an exhibition of it to this very day? and so with regard to other things, in many places, whose memorial endures beyond the term of their natural life. Therefore this acorn-bearing oak, on which once lighted “Jove’s golden Eagle, dazzling as the sun,” still flourishes before us. And when the storms of centuries shall have wasted it, there will still be found a relic on this sacred spot, which shall be called the Oak of Marius'

Richard Wilson, Cicero's Villa and the Gulf of Pozzuoli, 1770-80

%2C_Kunst-_und_Rarit%C3%A4tenkammer_(1636).jpg/1024px-Frans_Francken_(II)%2C_Kunst-_und_Rarit%C3%A4tenkammer_(1636).jpg)

_-_WGA03531.jpg)