Claude Monet, Étretat, la porte d'Aval: fishing boats leaving the harbour, c1885

This post begins with Claude Monet at

Étretat, a subject I've covered here before in '

The Cliffs at Etretat' and

'Agitated Sea at Etretat'. Guy de Maupassant watched the artist in action there in 1885 and described what he was like to the readers of Paris periodical

Gil Blas. 'At

Étretat I often followed Monet about. He was not so much a painter as a hunter. He stalked on ahead, followed by his children and Madame Hoschedé, who carried his canvases, sometimes as many as five or six, representing the subject at different times of the day and with different effects. He took them up and put them aside in turn, according to the changes in the sky. Face to face with his subject, the painter lay in wait for the sun and shadows, capturing in a few brushstrokes the ray that fell or the cloud that passed. I have seen him seize a glittering shadow of light on the white cliff and fix it in a flood of yellow tone which strangely rendered the surprising and fugitive effect of that elusive and dazzling brilliance. On another occasion he took a downpour beating down on the sea into his hands, and dashed it on

the canvas - and succeeded in really painting the rain as it seemed to the eye' (Bernard Denvir,

The Encyclopedia of Impressionism).

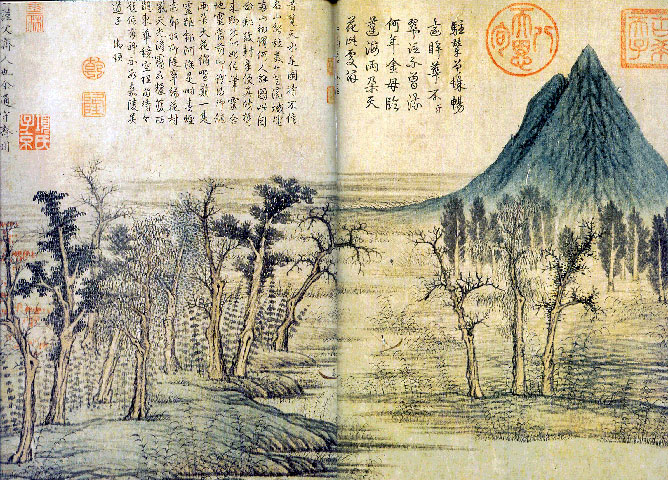

Claude Monet,

Sunset at Étretat, 1883

Maupassant lived in

Étretat as a child and in 1883 built himself

a house there (where, the following year, he finished writing there that most enjoyable novel,

Bel Ami). Just before this return, Maupassant published a sketch in the

Gaulois called '

The Englishman of Étretat'. This described his youthful encounter with the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne at the house of 'a young Englishman of unknown origin' who was rumoured in the village to diet 'exclusively upon monkey (whether, sautéed, roasted, boiled or preserved; no matter)'. Maupassant was invited to lunch by this eccentric individual after taking part in 'a rescue party formed for a friend of his, carried out to sea'. The friend was Swinburne, and he proceeded to dazzle Maupassant: 'His words issued forth with a shimmering vitality, galvanised by an imagination both clear and quick, but also hypersensitive and fantastical ... The house where these two men resided was a pleasant, if peculiar abode. The walls were replete with astonishing and strange paintings, veritable expressions of insanity. For instance, if my memory serves me correctly, one watercolour depicted a pink seashell carrying afloat a human skull upon an endless sea, beneath a moon of human form. Here and there were scattered skeletal remains. Particularly of note was a flayed hand; its desiccated skin intact, blackened muscles exposed and ancient traces of blood upon the bright white bone...'

![]()

Gustave Courbet, Cliffs at Étretat, 1870

I first came across this story in Charles Sprawson's

The Haunts of the Black Masseur: The Swimmer as Hero, a wonderful book published in 1992 which seems to have been rather overshadowed in recent years by Roger Deakin's

Waterlog. Iris Murdoch's

review of it sounded to me then charmingly eccentric: 'On hot days in the Oxford summer my husband and I usually manage to slip into the Thames...' Sprawson refers to Iris Murdoch as 'one of the last of the English river swimmers' and twenty years ago it would have been hard to believe that a whole movement would take off and there would be an

Outdoor Swimming Society (whose founder was, according to my wife, impressively outdoorsy even when they were studying at Oxford). Swinburne's passion for wild swimming began long before he went up to Baliol. Growing up on the Isle of Wight he would float in the sea, 'lapped in the blue waters and the languid summer tides, as though in the Aegean of his Hellenic dream-world'. Schooldays at Eton fostered a sado-masochistic association between flogging and swimming which surfaces in his later letters: Sprawson quotes one to Lord Houghton (who had already 'corrupted Swinburne by opening up to him his vast pornographic library'), regretting that the Marquis de Sade had not been aware of the punishment to be experienced in the waves of the North Sea. Swinburne enjoyed some 'delicious bathes in the most dangerous seas in the world' off Guernsey, having travelled there to meet his hero Victor Hugo only to find that he had left three years before. It was with some exciting passages from Hugo's novel

Toilers of the Sea that Swinburne entertained the fishermen rowing him back to safety at Étretat.

Victor Hugo, The Octopus,

a creature that appears in his novel, Toilers of the Sea, 1866

The lunch Swinburne and his strange friend, George Powell, invited Maupassant to on that memorable day is the subject of an article by Julian Barnes in the excellent

Public Domain Review. You can read there fuller details of the English couple's S&M activities with monkeys and servants, based on an account Maupassant gave to Edmond de Goncourt. Swinburne himself, by contrast, 'memorialised his time on the Normandy coast in two ways. For the rest of his life he kept the “outsize garments” (outsize because he was so tiny) in which the rescuing fishermen had dressed him. And in his 1883 collection,

A Century of Roundels, he published a poem called “Past Days”:

Above the sea and sea-washed town we dwelt,

We twain together, two brief summers, free

From heed of hours as light as clouds that melt

Above the sea.

The poem is partly a lament – for the dead Powell, and for passing time; also an idyll recreating “the days we had together” among “The Norman downs with bright grey waves for belt” and the “bright small seaward towns”. It is singularly lacking in references to monkey meat or Sadeian practices.'

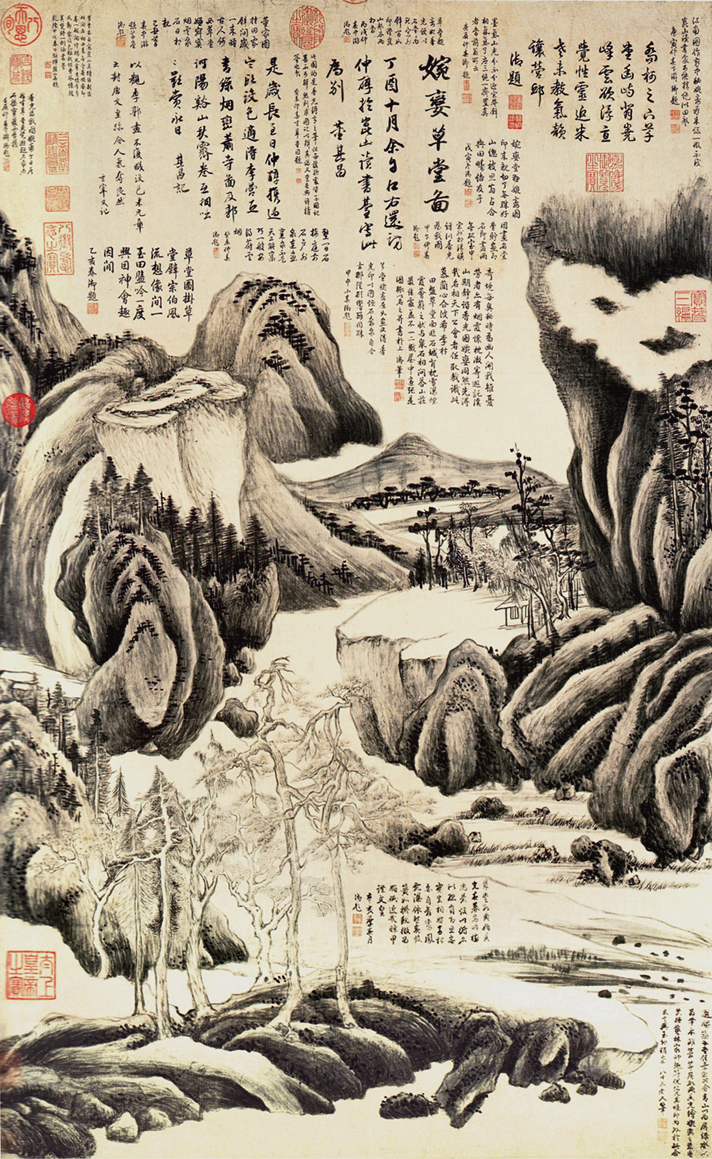

Gustave Courbet, The Wave, c. 1869

In 1869, a year after he helped rescue Swinburne from the waves, and long before he was an established writer ,spending time with Monet and his family, Maupassant encountered another visitor to Étretat, Gustave Courbet, and watched him at work in his studio. "In a big empty room, a huge man, corpulent and grubby, was using a kitchen knife to smear gobs of white paint on a big bare canvas. Every so often, he'd go and put his face to the window and stare at the storm. The sea came so close that it seemed to assail the house, covering it in spray and noise. The salt water beat like hail against the window panes and streamed down the walls. On the chimney a bottle of cider next to a glass half full. From time to time Courbet went and drank a few drops, then he came back to his work. Now, that work became

The Wave, and it created quite a stir in the world." William Feaver refers to Maupassant's description in a

review entitled 'Sea Power' and notes that 'being a romantic, Courbet took the wave personally. "In her fury," he told Victor Hugo, "she reminds me of a caged monster who can devour me. One feels carried away."'